Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is the most widely used form of 3D printing in households around the world. This process involves extruding melted thermoplastic material layer by layer, allowing each layer to cool and solidify before the next one is added.

FDM is an additive manufacturing method, opposite to subtractive processes like CNC milling. Instead of cutting away from a solid block, FDM uses only the material needed for the part itself, with the exception of support structures used for overhangs. These supports are removed and discarded after printing.

The uniqueness of FDM printing primarily lies in three key areas: the material used, the slicing software that converts 3D models into G-code instructions, and the extrusion system. Other components like motors and control boards are not exclusive to FDM and are common across many digital fabrication methods.

FDM printing is considered one of the most affordable and accessible methods of 3D printing. Compared to other technologies, such as SLA or resin printing, both the machines and materials are more cost-effective. While resin printer prices have dropped in recent years, they generally offer smaller build volumes and involve more expensive consumables, and are generally less user friendly.

The material variety available for FDM is extensive. Options include flexible filaments, carbon fiber blends, nylon, polycarbonate, UV-resistant, and weather-resistant materials. Many high-temperature materials are also available, though they often require enclosed and actively heated environments. With hundreds of filament types on the market—each offering unique characteristics like strength, flexibility, and thermal resistance—it is possible to find a material suited to nearly any application, provided the printer is equipped with a compatible extruder and hotend.

Compared to resin-based printing processes, FDM is also much cleaner and easier to use. It avoids handling of toxic chemicals and typically involves less post-processing. This makes FDM a more beginner-friendly option and better suited for casual or home use.

In FDM 3D printing, axis orientation may be unfamiliar to those with a background in geometry or general mechanics. The X-axis moves the tool left to right, the Y-axis moves it forward and backward, and the Z-axis controls vertical movement. Though it may seem counterintuitive, this naming convention is standard within the 3D printing community.

The most common axis configurations are based on Cartesian and CoreXY designs. Cartesian printers operate with each axis independently controlled by its own stepper motor. Typically, the build plate moves in the Y direction, while the hotend moves in the X direction. The entire carriage moves in the Z direction. These printers are often referred to as “bed slingers.”

Some machines, such as the Ender 5 series, use Cartesian-style motor movement but have a vertically moving build plate. These are often grouped with “gantry-style” printers for simplicity. In general, printers where the bed moves vertically in the Z-axis are considered gantry-style, while those where the bed moves forward and backward in the Y-axis are considered Cartesian-style or more colloquially as "bed slingers".

CoreXY machines differ in that the X and Y axes are synchronized through a belt system driven by two stepper motors. This allows for smoother motion, reduced Z-wobble, and improved stability—especially during faster printing. CoreXY printers are gaining popularity due to these benefits and are now found in models like the Bambu Lab X1 and P1 series.

Printers such as the A1 and A1 Mini continue to use Cartesian-style configurations and are known as "bed slingers".

Delta printers operate on an entirely different principle, using three arms arranged in a triangle to position the extruder above the print bed. While they can offer high-speed printing and excellent quality, they require taller frames and are less compact than Cartesian or CoreXY alternatives. These machines are far less commonly used due to space and setup requirements, but they are capable of excellent results.

FDM printers use one of two extruder types: direct drive or Bowden. A direct drive extruder feeds filament directly into the hotend from a motor mounted on the print head. In contrast, a Bowden extruder uses a remote motor to push filament through a PTFE tube to the hotend.

Bowden systems reduce the weight of the print head, allowing for faster movement. However, they can struggle with materials like TPU (flexible filament) and often require precise tuning of retraction settings to avoid stringing. Direct extruders offer better precision, easier use with flexible materials, and generally improved extrusion control.

Recent industry advances, such as vibration compensation, have made the weight disadvantage of direct drive systems less significant. As a result, more manufacturers are now offering affordable models with direct drive setups, and Bowden configurations are becoming less common.

Read more about Extruders.

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is an additive 3D printing process that extrudes melted thermoplastic material layer by layer, allowing each layer to solidify before adding the next.

Unlike subtractive methods like CNC milling, FDM only uses material needed for the part plus temporary supports, making it efficient and low waste.

FDM printing depends on three main factors: the filament material, the slicing software that produces G-code, and the extrusion system; other components like motors are shared with other fabrication types.

It is the most affordable and accessible 3D printing method, offering a wide range of materials including flexible, reinforced, and high-temperature filaments, suitable for both hobbyists and professionals.

FDM printers come in several motion systems: Cartesian (“bed slinger”), gantry, CoreXY (belt-driven synchronization for smoother motion), and Delta (triangular arm positioning for speed and precision).

Extruders are either direct drive (motor attached to the hotend for flexible filament control) or Bowden (remote motor for lighter, faster movements), with modern improvements favoring direct setups for versatility.

This Wiki is built with a very advanced where you can ask anything you want to know about. Just click the "Ask" icon at the top of this page, or hit "CTRL + I" on your keyboard.

This includes asking:

Just explain your application needs and ask the AI bot what material it suggests.

That's right - if the document exists on this Wiki - the bot will help you find it.

Wondering the material with the best HDT? The best impact strength? Ask away!

Just explain your issue and the bot will help diagnose the problem!

Ask the bot anything at all and feel free to let us know how it did! This is still a new feature and we would love your feedback. Shoot as an email anytime at [email protected] with how it did!

A slicer is specialized software that converts 3D models into printable instructions (G-code) for FDM printers. It "slices" digital designs into horizontal layers, calculates toolpaths, and defines parameters like print speed, temperature, and material flow. Slicers enable precise control over print quality, material efficiency, and structural integrity.

Model Import: Accepts 3D files (STL, OBJ, STEP, etc.) to define geometry.

Layer Segmentation: Divides the model into layers based on user-defined layer heights (e.g., 0.1mm–0.3mm).

Toolpath Generation: Maps extruder movements, including infill patterns, supports, and adhesion aids.

Parameter Configuration: Adjusts nozzle temperature, retraction, cooling, and material-specific settings.

Key features include infill density optimization, support structure generation, and print speed adjustments for balancing quality and efficiency.

Cardboard spools have several advantages over plastic spools that make them an appealing choice for many in the 3D printing community, despite some ongoing debate. One key benefit is their durability in terms of impact resistance—they do not shatter or crack when dropped, unlike plastic spools which can break. This toughness makes cardboard spools more resilient during handling and transportation. Additionally, cardboard spools can typically withstand higher temperatures before deforming, which is especially useful when drying filament spools prior to printing. Plastic spools may warp under such heat, whereas cardboard maintains its form better, allowing safer and potentially more effective moisture removal.

Another important advantage of cardboard spools is their environmental friendliness. Many cardboard spools, such as those produced by Polymaker, are made from recycled materials and are fully recyclable themselves. This contributes to reducing plastic waste and the overall carbon footprint associated with 3D printer filament packaging. They are lighter as well, which lowers shipping emissions. Cardboard spools represent a more sustainable option, aligning with the growing awareness of environmental impacts in 3D printing. Polymaker’s use of recycled cardboard further enhances this benefit, providing users with an eco-conscious choice without sacrificing functional durability.

To effectively dry your filament and achieve optimal results, having good airflow is far more important than simply increasing the temperature. This is because drying filament is primarily about removing the moisture trapped inside the material, and airflow plays a critical role in carrying away that moisture once it evaporates. As the saying goes, "you don't dry your hair by putting it in the oven," highlighting that excessive heat alone is not the answer and can even damage the filament if temperatures are too high.

By ensuring consistent and strong airflow, you can accelerate the drying process at a lower temperature, which is gentler on the material and helps maintain its quality. Good airflow allows moisture to escape efficiently, preventing it from lingering around the filament and causing issues like brittleness or poor print results. Overall, drying filament with proper airflow means you can dry it more quickly and safely, minimizing the risk of overheating while effectively preparing your filament for smooth, reliable 3D printing.

When 3D printing, layer height and part thickness can influence more than just strength and weight. The thickness of a print plays an important role in how well it holds its shape under heat, whether during service use or during post-processing such as annealing. Heat deflection temperature (HDT) is often discussed when comparing materials, but the print’s geometry and density also have a large effect on real-world performance.

Download the slicer profile you want to use, making sure it’s compatible with your slicer and printer model. The file is often in formats like .ini, .json, .3mf, .zip, or a specific profile extension.

Open your slicer software and find the menu option for importing profiles—this is usually under “File” or “Settings,” then “Import” or “Profiles.”

Importing a profile onto a slicer will be different depending on the slicer you are using. For the example below we will use Bambu Studio.

After downloading your profile from our list, you will open up Bambu Studio. You then click on "File" on the top left:

You then scroll over "import" and click "Import Configs"

You will then either choose the Zip file or the .bbsflmt file you just downloaded. If the profile you downloaded is a Zip file - you would choose the zipped compressed folder without uncompressing.

Your profile will now be listed under "User Presets" "Custom"

In 3D printing, the term "jerk" has a different practical meaning compared to its classical definition in engineering and physics. Traditionally, jerk is defined as the rate of change of acceleration—a third derivative of position with respect to time, measured in units like mm/s³. It describes how quickly acceleration itself changes, which is a highly dynamic, instantaneous measure important in motion control and mechanical systems.

However, in 3D printing firmware and motion control, "jerk" is commonly used as a simplified setting representing the instantaneous allowable speed change of the printer's print head when changing direction, measured in mm/s (velocity units, not acceleration units). It effectively sets a threshold speed—the maximum speed at which the printer can change direction without needing to decelerate to a full stop first. For example, if the jerk is set to 20 mm/s, the printer can instantly reverse or turn at that speed without slowing down completely, enabling smoother and faster cornering movements. This usage is more about limiting abrupt speed changes in the axes at junctions or corners rather than describing physical jerk as acceleration changes. Thus, in 3D printing, jerk controls how quickly the print head can pivot direction, affecting print speed, quality, and mechanical vibrations, rather than representing true "jerk" from physics.

Many people don’t usually consider PLA to be weather resistant because it is well-known for having a relatively low heat resistance compared to other engineering plastics. However, PLA can actually exhibit surprisingly good resistance to UV exposure and various weather conditions when it is formulated and processed correctly. While traditional PLA may degrade more quickly under prolonged sunlight or outdoor exposure, specially engineered PLA variants can hold up much better in these environments than commonly assumed.

For example, Polymaker’s Matte PLA for Production has been subjected to rigorous weather resistance testing, which demonstrated that it performs on par with ASA, a material widely recognized for its excellent UV and weather durability. This means that, despite the typical perception of PLA as a material better suited for indoor or low-stress applications, certain advanced PLA formulations like Polymaker’s Matte PLA can be confidently used for outdoor projects or parts exposed to sunlight without rapid degradation. This opens new possibilities for using PLA in functional applications where both aesthetic finish and environmental resistance are important.

The first layer of a 3D print is arguably the most critical, as it sets the foundation for the entire part. If the first layer does not adhere properly to the build plate or is unevenly extruded, the print can fail as subsequent layers rely on a stable and consistent base. Too large a gap between the nozzle and the bed can lead to poor adhesion, resulting in warping or layer shifting, while a nozzle too close to the build plate risks scraping or damaging the surface, potentially ruining both the plate and the print. A well-laid first layer ensures proper bonding and dimensional stability, significantly increasing the chances of a successful print.

Modern 3D printers have made significant advancements with features like automatic bed leveling and initial Z-height calibration, which greatly reduce the chances of first layer issues and save users from manual tweaking. These automated systems help ensure the nozzle height and bed level are optimized before printing starts. However, despite these improvements, it is still highly recommended to monitor the first layer closely, especially when trying a new material, changing build plates, or printing after maintenance. Confirming the first layer prints correctly before leaving the printer unattended remains best practice to prevent print failures and protect your hardware.

Many people in the 3D printing community often consider standard PLA to be a weak or fragile material. However, this perception doesn’t tell the full story. In reality, standard PLA exhibits impressive strength in several important mechanical aspects. It is known for being very rigid and having good tensile strength, allowing it to withstand substantial loads and maintain its shape under pressure. This makes PLA well-suited for many applications where stiffness and dimensional stability are critical.

The misconception about PLA’s weakness largely stems from its relatively low impact resistance. While PLA can handle steady forces and tension well, it is more prone to cracking or breaking when subjected to sudden impacts or drops. This means that although a PLA print might not bend or deform easily under normal use, it can be brittle when faced with sharp shocks or accidental falls. Therefore, impact resistance is just one way to measure material strength, and PLA’s excellent rigidity and tensile capabilities mean it can be quite strong when used in the right contexts and for parts designed to avoid impact stresses.

Launch Cura on your computer.

In the top menu, click Preferences, then select Configure Cura. This opens the main configuration panel where you can manage profiles and materials.

On the left side of the configuration panel, click Profiles to see your current list of available print profiles.

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) describe the same 3D printing process, which involves extruding thermoplastic filament layer by layer to build a part. The method has become one of the most widely used additive manufacturing techniques because of its relatively low cost, material availability, and accessibility to both hobbyists and professionals. Despite the different names, the underlying process is identical in both cases.

The distinction between the terms comes from intellectual property rather than technology. Fused Deposition Modeling was coined and trademarked by Stratasys, one of the pioneering companies in the 3D printing industry. Because the name is protected, the broader community, particularly in the open-source sector, adopted the term Fused Filament Fabrication to describe the same process without infringing on trademark rights.

Today, both FDM and FFF are used interchangeably to describe extrusion-based 3D printing. In commercial and industrial contexts, FDM may be more common, especially when referring to Stratasys machines, while FFF is often seen in reference to open-source or consumer-grade printers. Regardless of terminology, the technology refers to the same foundational process in additive manufacturing.

G-Code Export: Generates machine-readable instructions for the printer.

Select “Import,” then browse to and select your downloaded profile file.

Confirm the import; your new profile should appear in the list of available print, filament, or machine profiles, ready to be selected for your next print job.

For some slicers, you may need to activate or assign the profile to a printer or filament type after importing.

Always double-check print settings after importing to ensure compatibility with your printer and material, as profiles are sometimes designed for specific setups.

Following these steps works for popular slicers such as Cura, PrusaSlicer, Bambu Studio, OrcaSlicer, and ideaMaker.

A file browser window appears. Navigate to the profile file you wish to import (typically .curaprofile or .json format) and select it. Click Open.

Cura will show a dialog confirming the imported profile. You will now see the new profile listed under Custom Profiles.

Click the Activate button on your new profile to begin using it for slicing prints.

If you want to access more or advanced settings, in the Profiles section, you can check or uncheck which parameters display during regular use.

To use the imported profile, make sure it’s selected before you prepare or slice your next model.

These steps will look very similar across current Cura versions. The interface is straightforward, with dialogs or panels appearing as you follow each menu path and choose your import option.

3MF: A newer file format designed specifically for 3D printing. It is basically G-code along with other relevant slicing information so that you can open a 3MF file into a slicer.

Aluminum Extrusion Rails: These have your carriages move along aluminum extrusion bars via rollers (as compared to Linear Rails or Linear Rods). Think of the original Ender 3 as an example.

Barrel: A heatsink attached to your hotend which is meant to keep a temperature differential from said hotend. The barrel is cooled by a fan and will make sure your filament is only being heated in the hotend and not creeping upward.

Bowden Extruder: An indirect extruder – where the extruder is not directly attached to the hotend and must feed filament over a distance to reach the hotend.

Brim: Lines of print that are touching the perimeter of your print on the build plate. This helps to anchor your part if you think it may warp or get knocked off.

Cartesian: A printer where each axis is controlled and moved independently by a motor. The X-axis operates autonomously from the Y-axis. The Bambu Lab A1 is an example of a cartesian machine.

Cooling Fan(s): The fans used to cool the printed layers quickly to improve print quality. These fans help surface and overhang quality but can increase your chances of warping and delamination on some higher temperature resistant materials.

CoreXY: A printer that synchronizes the X and Y axes movement via stepper motors. When the hotend moves in the X-direction, both motors rotate, and the same applies to the Y-direction. Bambu Lab P1 and X1 printers are examples of CoreXY machines.

Direct Extruder: This is an extruder that feeds directly into the hotend without any added distance.

Endstop: The part that is triggered when you reach the furthest point of your build volume in any direction. This trigger tells the printer it cannot move any further and is used to “home” your machine.

Extruder: The part of the printer that pushes or feeds filament. It is motorized.

Filament: Strands of material – it can be thought of as another term for the material being used in your 3D printer.

Firmware: The software that is embedded into your printer to tell it how to operate. This can either be open-source (Marlin/Klipper) or closed-source.

G-code: The file format used to tell your printer how to move, how fast to move, and how much material to extrude. Slicers turn 3D models into G-code, but you cannot open G-code in a slicer and edit any settings – that would require a 3MF file format.

Gantry Style Printers: This is a term that is may not be being used correctly, but it is how we refer to any machine that moves the build plate up and down in the Z-direction. Can include CoreXY machines like the Bambu Lab X1C, or a Cartesian one like the Ender 5.

Hotend: The part of your printer that melts the filament. It is powered by a heater and uses a thermistor to tell the temperature.

Hygroscopic: How likely your material is to absorb and be affected by moisture. The more hygroscopic the material, the more susceptible it is – meaning the more likely it will need frequent drying.

Jerk: The instantaneous velocity your printer will start at after a directional change or after reaching a full stop. In engineering this refers to something else, but in 3D printing this is what the word means.

Infill: The internal structure of a printed object, typically designed to add strength while reducing material usage and print time.

Layer Height: The thickness of each individual layer of your print. Lower layer heights normally means greater Z-axis detail - but will also result in a print that takes longer to complete.

Leadscrew: A threaded metal part that turns to move an axis by being attached to a stepper motor. These are normally used for the Z axis on printers rather than a belt.

Linear Rails: These use a stiff, steel rail along which the carriages slide via bearings (as compared to Aluminum Extrusion or Linear Rods).

Linear Rods: These have the carriages attached to a smooth rod via bearings (as compared to Aluminum Extrusion or Linear Rails).

Nozzle: A die that is attached to your hotend that will set the diameter thickness of the individual lines for material you are extruding. Common nozzle diameters are between 0.15mm and 1.2mm – though they can come in nearly any size. The larger the diameter – the better the hotend you will require to print fast to heat the material to the proper viscosity. Generally speaking smaller diameter nozzles can result in more X/Y detail, while larger nozzles can usually result in better layer adhesion.

Raft: An initial few layers of material that will be removed after printing, to help the main part of your print stick properly. These are rarely used but can help in certain situations.

Slicer: The software used to convert a 3D model into G-code or a 3MF file.

Skirt: A small amount of purge material that lays around the perimeter of your print on the build plate, but does not touch the print itself. This is solely to make sure your material is printing properly before starting a print but does not add any extra build plate adhesion.

Stepper Motor: Motors used to move your different axes as well as your extruder.

Supports: Temporary structures generated by the slicer software to support overhanging features of a printed object during printing. These can be thought of as scaffolding for your print.

Thermistor: A thermostat which will tell the temperature of your hotend (or possibly your build plate). It will tell your printer if you are below your set temperature or if you have reached it. A malfunctioning thermistor without proper safety software built in can be very dangerous.

Travel: This refers to when your printer is moving between parts of your print and is not actively extruding/printing.

Volumetric Speed: The maximum volume of material that the printer can extrude per unit of time, considering nozzle diameter and layer height.

Make sure you have downloaded your profile files, which are usually in .ini, .gcode, or .3mf format. Extract the files if they come in a zip.

Launch PrusaSlicer and look for the top menu bar.

Click File, then select Import.

If you are loading a single profile, choose Import Config. To bring in multiple profiles at once, use Import Config Bundle.

For project files saved from PrusaSlicer (.3mf or .amf), select Import Config from Project.

Browse to the location where your profile file is saved and select it. The profile may contain Print, Filament, and Printer settings.

PrusaSlicer will import and add the new settings as custom profiles under the relevant section: Printer, Filament, or Print Settings.

You should now see the imported custom profile in your lists. Select the new preset as needed for your print job.

Always double-check that the settings match your machine and material to avoid accidental misconfiguration.

If you download a profile with a .txt extension, rename it to .ini before importing.

After importing, review the settings and, if needed, fine-tune for your particular application or printer.

This procedure supports importing profiles for a wide range of printers and materials, and keeps your settings organized for easy use and future reference.

Thin-walled or low-density prints are more prone to warping and deformation when exposed to heat. Because the structure has less material to resist internal stresses, it will soften faster and lose its shape more easily. This is especially noticeable when annealing thin models since the plastic relaxes as internal stresses are released.

For this reason, extra measures should be taken when working with and annealing thin parts. Two common methods are salt annealing or sand annealing, where the print is buried in fine grains to hold it in place while it heats. If the print is flat, placing a weight on top can help keep it from bowing or curling during the process. These methods reduce unwanted distortion and allow the heat treatment to improve thermal resistance without losing dimensional accuracy.

Thicker, denser parts behave differently under heat. Because they have greater bulk and structural integrity, they are more resistant to softening and warping during exposure. A heavy, solid print will generally hold its shape without needing to be supported during annealing. While the annealing process can still improve heat resistance by increasing crystallinity in certain materials, the odds of geometric deformation are much lower compared to thin-walled prints.

The heat resistance of a printed object cannot be determined by material rating alone. While HDT gives useful baseline information, geometry and thickness contribute to how that object will perform in practice. A thin tray and a solid block made of the same filament can show very different behaviors when placed under heat. Understanding this relationship makes it possible to choose the right print settings, infill, and post-processing method to get the desired thermal performance.

Maintaining a 3D printer involves regularly scheduled tasks and readily available supplies to prevent issues and ensure optimal performance. Certain tools are used frequently, while others are reserved for occasional maintenance.

Specific tools enhance 3D printing and printer maintenance.

Pliers: Indispensable for removing support material from prints, pliers also assist in holding components during tasks like nozzle replacements.

Razor Blade: Useful for cleaning up prints, especially for removing brims and tidying rough edges or stringing. Exercise caution when using.

Model Cutters: Thin, sharp scissors are essential for delicate prints, especially when removing support material from fragile sections.

Scraper: A sturdy metal scraper with a tapered front improves usability and durability for removing prints from the build plate.

Metric Allen Screwdriver Set: Essential for accessing and maintaining various components of the printer. Common sizes include M2.5, M3, M4, and M5. A color-coded set can help easily identify each size.

Solder Set or Solder Seal Wire Connectors: Soldering equipment is essential for repairing frayed wires and making electrical connections. Solder seal wire connectors provide a secure solder-free alternative. While potentially unnecessary for closed-source printers, soldering equipment is useful to have on hand.

Tweezers: Fine-tipped tweezers are useful for removing excess material or debris from prints, particularly during the printing process.

Zip Ties: Helpful for securing cables and organizing wires within the printer.

Calipers: Accurate measurement tools are essential for precise modeling, filament measurement, and determining E-steps.

Multimeter: Invaluable for diagnosing electrical issues, particularly for checking continuity and voltage.

Loctite Super Glue Gel or 3D Gloop: Fast-drying adhesives ideal for minor repairs on PLA prints, providing a strong and durable bond.

White Lithium Grease: Regularly lubricating threaded and smooth rods helps ensure smooth and consistent operation.

Wire and Nylon Brushes: Nylon brushes clean dirty nozzles and heater blocks, while brass brushes address more stubborn residue, used sparingly due to potential abrasion.

Having certain inexpensive components on hand can minimize downtime.

Thermistors: These components function as thermometers for the hotend, ensuring proper temperatures. Keeping spares handy addresses temperature-related errors.

Heater: While heaters don't require frequent replacement, having a spare is useful in troubleshooting hotend heating issues.

Nozzles: Stocking up on replacement brass or hardened steel nozzles addresses print quality issues caused by wear. It is useful to have a set of hotend/nozzle combinations for closed-source machines for easy swaps.

Investing in these spare parts can minimize downtime and address issues during 3D printing.

The image below is a printer in a Cartesian setup, where the build plate moves back and forth in the Y direction and the hotend left and right in the X direction – similar to the popular Bambu Lab A1, Creality Ender 3, and Prusa MK4 printers.

Z Carriage: This connects to both the Z rod and threaded rod/leadscrew. The leadscrew then turns due to the stepper motor it is attached to, which then moves the x carriage up and down. On Bowden machines this is often where the extruder is attached.

X Endstop: This is what tells the hotend to stop when homing. There is also a Y and Z endstop not shown in this picture which have the same function (though a Z endstop may be replaced by an auto bed leveler).

Build plate: This can be either glass, PEI, or another form of build plate. This is where the prints stick to.

Nozzle: Filament is fed through a heated nozzle in order to form your print. These can be found with different diameter holes, with the smaller the hole, the finer the detail. Nozzles range from 0.15mm – 1.2mm in diameter (sometimes thicker with hotends such as the SuperVolcano). They also come in brass, hardened steel, and ruby tip, with each becoming more abrasive resistant and more expensive.

X Carriage: This is where the hotend (and printers with direct extruders) attach to. The X carriage is attached to the X rods and belt which then in turn move the hotend in the X direction. This carriage should be very secured and not have any rattling.

Extruder: This is how the filament is fed into the nozzle. In this example we are showing a non-geared direct extruder. A geared extruder will have a gear-ratio allowing for less stress to be placed on the stepper motor, adding a mechanical advantage for more torque, allowing the filament to be fed faster. The extruder includes a tooth drive attached to the stepper motor that pinches the filament against a bearing that freely spins. There are dual drive extruders as well which replace this bearing with another tooth drive. This extruder can also be placed on the Z carriage in a Bowden fashion.

Extruder Stepper Motor: The extruder stepper is what turns and feeds filament through the extruder. This would be placed on the Z carriage when on a Bowden setup. This is what you are controlling when you set the E-Steps. When using a geared-extruder, you put less strain on this stepper motor by giving it a mechanical advantage, which would result in less extruder motor skips and a higher E-Step value. It would be smart to place a heat sink on this in order to disperse heat if you built your printer. This added weight when setup in a direct fashion can be one reason someone would prefer Bowden.

X Carriage Belt: This is what is connected to the X carriage as to move it left and right in the X direction via a stepper motor. This belt should be tight/springy to the touch as to reduce Z-wobble.

Y Stepper Motor: This stepper motor moves the bed back and forth in the Y direction by controlling the Y carriage belt. This is only present in this fashion on Cartesian machines. Remember on CoreXY setups, there is no “Y stepper Motor” as each motor moves both the X and Y axis dependent on one another.

Y Carriage Belt: This is the belt that is connected to the build plate and is controlled by the Y stepper motor and spins freely attached to a bearing on the other side. Just as with the X carriage belt, this should be tight and springy to the touch.

Y Smooth Rods: These rods are what the Y carriage are attached to via bearings and are smooth to the touch. They help to make sure the build plate moves smoothly back and forth without rattling. These rods should be lubricated with white lithium grease so that the build plate can move without resistance. These can be replaced with a rail system or aluminum extrusion with rollers instead on particular machines.

Active Cooling Fan: This fan is used to cool prints as layers are being laid down. This is crucial to use to get clean prints with particular materials, including PLA. This can lead to decreased layer adhesion on other particular materials, so you need to confirm the material you are using before turning it on in your slicer settings.

Z Stepper Motor: On some machines there is only one Z stepper motor, but there are dual steppers in this example. This stepper motor turns the Z leadscrew (or thin threaded rod) and moves the X and Z Carriage up and down, via where it is connected to the Z carriage (1 in photo). This is different on CoreXY machines, since those move the build plate up and down instead of the hotend.

Heaterblock of Hotend: This is the part of the hotend that gets hot and is attached to the heater. This is attached to the nozzle below it, and the barrel above it (with a heatbreak in between). The barrel should always have a fan blowing on it to prevent heat creep, though one is not shown in this picture.

X Smooth Rods: These rods are what the X carriage via bearings and are smooth to the touch. They help to make sure the hotend move smoothly left and right without rattling. These rods should be lubricated with white lithium grease so that the carriage can move without resistance. These can be replaced with a rail system or aluminum extrusion with rollers on particular machines.

Z Smooth Rods: There may only be one of these on your machine, but in the photo above, there are two Z smooth rods. These are what your Z carriage is attached via bearings to in order to ensure the Z carriages are moved up and down smoothly without rattling. They should remain lubricated just like the X and Y smooth rods as to ensure there is as little friction with the bearings as possible. These can also be replaced with a rail system or aluminum extrusion with rollers on particular machines.

Z Leadscrew (or threaded rod): These are threaded rods ranging from 5mm-10mm in diameter, with 8mm seeming to be the most common. Many machines only have one of these, but I have found when there are dual leadscrews you get more consistent results. These are turned via the Z stepper motors which then thread into the Z carriages – moving the Z and X carriages up and down. These have essentially the same function for the Z carriages as the belts have for the X and Y carriage. They are threaded rods though because more weight is placed on these parts, and less frequent moving is required out of the Z direction. In general, the thicker these leadscrews are, the better. Thin 5mm threaded rods can become bent and do not last long on 3D printers.

When orienting prints on the build plate, it’s common practice to prioritize factors like achieving the best overhang quality and minimizing the amount of support material needed. While these considerations are important for print quality and efficiency, they are not the only elements to keep in mind when deciding on the print orientation. One crucial factor that is often overlooked is the mechanical strength of the printed part, which is inherently influenced by the layer-by-layer nature of 3D printing.

Because 3D prints are created by stacking layers of material, parts typically exhibit their weakest mechanical strength along the Z axis—perpendicular to the layers—making them more prone to breaking or delaminating along those layer lines. As a result, if you're printing a part that must withstand mechanical stress or structural loads, it’s essential to carefully consider the orientation not only during printing but also during the design phase. By aligning the print so that the greatest stresses are along the X or Y axes (parallel to the layer lines), you can significantly improve the part’s durability and performance. Taking print orientation into account from the start can help ensure the final object meets both functional and strength requirements.

Setting your maximum volumetric speed (MVS) is a crucial step in optimizing 3D print quality and preventing under-extrusion. Volumetric speed represents the rate at which your printer’s hotend can reliably melt and extrude filament, measured in cubic millimeters per second (mm³/s). When you set a cap on the MVS in your slicer, your printer will automatically adjust the movement speed based on your chosen layer height and line width. The slicer calculates the resulting maximum speed using the formula: Print Speed (mm/s) = Volumetric Flow Rate (mm³/s) / (Layer Height (mm) × Line Width (mm))

You can also use THIS handy calculator.

If you increase either the layer height or line width (common with larger nozzles), the maximum print speed is automatically reduced to prevent exceeding the hotend’s capacity. For example, with a higher layer height or wider extrusion, your print speed must decrease to maintain the same volumetric flow, ensuring consistent, high-quality extrusion and avoiding issues like gaps, jams, or weak prints.

This approach is more robust than simply setting a maximum “print speed” in mm/s. Linear print speed alone does not account for how much material is being deposited per second: with a large nozzle or big layer height, the filament volume per second can easily surpass what the hotend can handle even at modest print speeds. By capping the MVS, your printer will slow down automatically for thicker lines or layers, yet speed up when printing thinner or finer layers—all while staying within safe extrusion limits for your specific printer and filament. This adaptive control makes volumetric speed a far more representative metric for maximum throughput than just relying on linear print speeds, especially for advanced users who frequently change nozzle size or print settings.

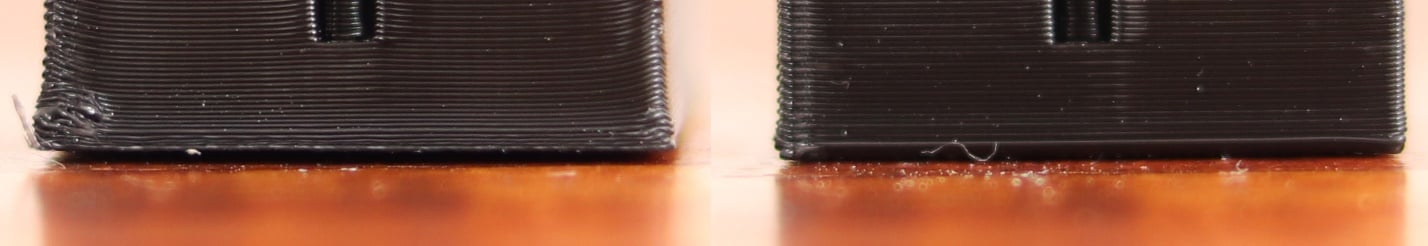

Over-extrusion in 3D printing is generally easier to detect with the naked eye than under-extrusion. When too much filament is extruded, you often see obvious signs like blobs, stringing, or excessively thick layers where the filament appears to spill or ooze beyond the intended boundaries. These visual cues—such as raised ridges between surface lines or drooping layers caused by excess material—make over-extrusion relatively straightforward to identify. The surface of the print may look messy or oversized, which indicates that the printer is pushing out more material than necessary.

In contrast, under-extrusion can be subtler visually but can have a more serious impact on print strength. Even if an under-extruded part looks acceptable on the surface, missing or thin filament deposition means the layers are not fully bonded, and the internal structure can be fragile. This results in prints that crumble, crack, or tear more easily under stress, since insufficient filament compromises the object's mechanical integrity. Gaps between layers or sparse infill may not always be immediately apparent, but they weaken the part significantly. So while under-extrusion can be harder to spot at a glance than over-extrusion, it poses a greater risk to the durability and functionality of the final print. Monitoring print quality with attention to detail is necessary to avoid these hidden weaknesses.

This means visual inspection alone might not detect under-extrusion sufficiently, making calibration and careful tuning essential for strong, reliable 3D prints. Over-extrusion errors warn you visually that something is wrong, but under-extrusion can quietly degrade part quality even if it looks good initially.

Tree supports and normal (or linear) supports represent two distinct types of support structures used in 3D printing to handle overhangs and complex geometries, each with their own pros and cons. Tree supports grow organically around the model, starting with a thick base on the build plate and branching out to support overhangs only where necessary. This tapered, hollow design uses less filament and typically reduces print time compared to normal supports. Because tree supports touch the model at fewer points—often just at the tips of their branches—they generally cause less surface damage and are easier to remove. Additionally, since tree supports primarily attach to the build plate rather than the print itself, there is a lower chance that support material will be deposited directly atop the model, improving the final surface finish on supported areas. However, tree supports have less surface area to support overhangs, which can sometimes result in weaker support for delicate features or a worse looking underside of your print. They are also more prone to being knocked off the build plate during printing, especially if the base is narrow or the print is tall and wobbly.

Normal supports, on the other hand, consist of vertical structures printed straight up from the build plate directly underneath overhangs. These supports provide a larger contact surface area with the underside of overhangs, often leading to better overhang quality by offering solid, stable backing during printing. They are less likely to detach from the build plate mid-print, providing more reliable support for heavy or extensive overhang areas. The downside is that normal supports consume more filament and typically lengthen print times due to their denser, solid design. Moreover, normal supports often touch the print’s upper surfaces, which can leave marks or require more post-processing to achieve a smooth finish.

Many modern slicers offer a hybrid support option that combines the benefits of both systems. In hybrid mode, the slicer generates tree-like supports farther from the model to save material and reduce print time, and gradually transitions to normal supports as it approaches the model surface to provide a sturdier, larger contact area for better overhang support and easier removal. This approach captures most of the advantages of both support types—minimizing filament usage and print time like tree supports while maintaining the stronger, more reliable interface with the print that normal supports provide. Hybrid supports therefore offer a versatile solution for complex prints requiring careful balance between material efficiency and surface quality.

Composite 3D printing remains an exciting and relatively untapped area within the 3D printing world. While it has not yet been fully explored or mainstreamed, the ongoing development and increasing availability of multi-tool and multi-material printers are paving the way for truly innovative and complex composite prints. As these advanced machines become more accessible, we can expect to see groundbreaking combinations of materials that were previously impossible or impractical to combine, pushing the boundaries of what 3D printing can achieve.

At its core, composite 3D printing involves using two or more distinct materials within a single print to produce parts that possess enhanced or hybrid properties, leveraging the strengths of each individual material. For example, by combining flexible TPU with rigid PLA in one object, engineers can create components that are not only strong and durable but also capable of withstanding impact and absorbing energy—so much so that such prints can even stop a bullet in certain experimental applications. This ability to tailor mechanical, thermal, or chemical properties on a layer-by-layer basis opens up exciting opportunities in fields ranging from protective gear to custom medical devices and beyond. As the technology matures, composite 3D printing is set to revolutionize how we think about material performance and design freedom.

Also known as Thermoplastic Polyurethane

Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) has revolutionized 3D printing with its unique blend of rubber-like flexibility and industrial-grade durability. Known for its shock absorption, chemical resistance, and stretchability, TPU is the go-to filament for functional parts that demand elasticity without sacrificing strength. From custom phone cases to automotive seals, TPU unlocks applications where rigidity fails.

TPU is a flexible thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) that combines the elasticity of rubber with the printability of plastic. Unlike rigid filaments, TPU can stretch up to 500% of its original length before breaking, making it ideal for bendable, impact-resistant components. Its durability against abrasion, oils, and low temperatures further cements its role in industrial and consumer applications.

Wear resistant 3D printing materials are essential for parts that must withstand friction, abrasion, and mechanical stress over time. Selecting the right material ensures longer component lifespan and reduces maintenance needs. Different filaments offer various levels of wear resistance, impacted by both chemical composition and the presence of added fibers or lubricants.

Nylon: Known for its toughness, semi-flexibility, and high impact and abrasion resistance. Nylon is a standout choice for functional and moving parts, such as gears and bushings, especially when reinforced with carbon or glass fibers for even greater durability.

Print quality and printing time depend on several factors, with nozzle diameter and layer height having the most significant impact.

Nozzle diameter determines the line width of printed segments, which affects tolerances in the X/Y direction. While some users adjust line width slightly, maintaining the same value as the nozzle diameter is common. Experimenting with a 10% increase has produced favorable results (e.g., printing a 0.44mm line width with a 0.4mm nozzle).

Any section of the print narrower than the line width will not be printed; therefore, a thinner nozzle diameter can lead to higher print quality. Certain slicer settings may allow for printing thin walls, though dimensions smaller than the line width may not be accurate.

Layer height significantly impacts print quality and duration, with optimal ranges dictated by nozzle diameter. A 0.1mm layer height triples print time compared to 0.3mm when using the same nozzle and speeds, as it requires three times the number of layers. Reliable results are achievable within 25–75% of the nozzle diameter (though some suggest 20-80%):

Example: A 0.4mm nozzle performs best at 0.1–0.3mm layer heights

3D printers are categorized by their motion systems, which dictate how the print head and build platform move during printing. Among various motion systems, the three primary types are Cartesian, CoreXY, and Delta. While other motion systems exist, these three are the most common and widely used in desktop 3D printing.

Besides Cartesian, CoreXY, and Delta, there are other motion systems such as Polar printers, SCARA (Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm) printers, continuous belt, and H-Bot systems. However, these are less common in consumer and hobbyist 3D printers.

Fiber-reinforced materials such as carbon fiber (CF) and glass fiber (GF) composites offer excellent stiffness, strength, and dimensional stability, but they also tend to be more brittle on the spool than base polymers. This brittleness means certain precautions must be taken when handling and printing these materials to prevent filament breakage and ensure consistent extrusion.

Electrostatic Discharge (ESD) safe 3D printing materials are specially engineered polymers designed to safely dissipate static electricity, protecting sensitive electronic components and assemblies from damage caused by sudden static discharges. These materials incorporate conductive additives like carbon nanotubes or carbon fibers, which provide controlled electrical conductivity or electrostatic dissipation.

Static electricity buildup can harm delicate electronic circuits and components during manufacturing, assembly, or handling. Using ESD safe materials for 3D printing jigs, fixtures, housings, and tools helps prevent electrostatic discharge events that can degrade or destroy sensitive electronics. This protection is critical in industries like electronics manufacturing, clean rooms, aerospace, and automotive sectors where reliability and safety are paramount.

When selecting 3D printing materials for electrical insulation applications, understanding key electrical properties such as dielectric strength and dielectric constant is essential. These properties determine how well a material insulates against electrical voltage and how it interacts with electrical signals, impacting safety, signal integrity, and overall performance.

Dielectric strength measures how much voltage a material can withstand per millimeter before electrical breakdown occurs, essentially how well it resists electricity passing through it. A higher dielectric strength indicates better insulating capability. Fiberon PPS-GF20, reinforced with 20% glass fiber by weight (GF), exhibits a dielectric strength of approximately 6.05 kV/mm. This is about 12 times higher than Fiberon PPS-CF10 (carbon fiber reinforced), which has 0.45 kV/mm. The significantly elevated dielectric strength of PPS-GF20 makes it highly suitable for moderate voltage insulation, ensuring safer operation compared to carbon fiber reinforced materials or air in many applications.

Reducing purge waste on an AMS or similar multi-material system can make a significant difference in both material savings and print efficiency. Multi-material FDM printers use purge cycles to clear previous filament from the hotend during color or material swaps, but there are practical strategies to minimize this waste.

The most effective way to reduce purge waste is to use a printer equipped with more than one hotend and nozzle. IDEX (Independent Dual Extruder) and tool changer systems keep each filament assigned to its own hotend, minimizing the need for purging during swaps. Dual-head and similar machines provide much lower waste than single-nozzle systems that rely on AMS, MMU, ERCF, or Palette units.

Open ideaMaker on your computer.

Click the Library button in the top toolbar to access the ideaMaker Library.

Browse or search in the Library for the slicing profile you want to import.

On the profile detail page, click “Import to ideaMaker.”

Currently, we do not have any data confirming that any 3D printing material is FDA food-safe. In fact, no 3D printing material on the market holds FDA food-safe certification. This is because food safety certification applies not only to the raw material but to the final printed object itself. Factors such as the object's shape, the type of build plate used, the printing environment, and the entire manufacturing process all affect whether the object can be deemed food-safe. At present, the FDA does not offer a specific certification tailored for 3D-printing materials.

Even if the filament material itself is considered food-safe, the 3D printing process usually compromises that safety. The layered nature of fused filament fabrication creates microscopic gaps and crevices between layers, which can easily harbor bacteria and contaminants. These tiny spaces make thorough cleaning extremely difficult, so while the object might be safe for a single use, reliably sanitizing it for repeated food contact is challenging. Additionally, the use of brass nozzles in printing can introduce another safety concern. Brass contains lead, and during the printing process, small amounts of lead may be transferred onto the surface of the print. This contamination makes the printed part potentially unsafe for food use as well. Because of these factors—including material, process, and equipment—it is important to approach 3D-printed objects with caution when considering them for any food-related application, often necessitating additional post-processing, sealing, or certification to ensure safety.

Quality vs. Speed: Thicker layers reduce detail in the Z axis but accelerate printing, while thinner layers enhance Z resolution at the cost of time.

Print duration also influences failure likelihood. Longer prints increase exposure to environmental variables (e.g., temperature shifts, power interruptions). Additionally, extrusion speeds often need reduction for thinner layers to prevent nozzle clogs or under-extrusion. Conversely, very large layer heights may also require reduced speed due to the max volumetric speed of your material and/or hotend.

Generally speaking - modern printers are not as affected by what is covered below, but it still can be beneficial to understand it.

Layer height precision is affected by Z-axis leadscrew/threaded rod specifications, including pitch and motor step angle. Mismatched settings can introduce inconsistencies due to mechanical rounding errors. For example:

M8 Leadscrew (2mm pitch): Adjustable in 0.01mm increments with a 1.8° stepper motor.

M5 Leadscrew (0.8mm pitch): Requires adjustments in 0.014mm increments for optimal precision.

These tolerances matter most on budget machines, where hardware limitations amplify imperfections. While deviations from calculated values may yield acceptable results, adhering to mechanical constraints ensures maximum consistency.

The initial layer height prioritizes adhesion over detail. A thicker first layer (up to 75% of nozzle diameter) improves bed bonding by increasing material deposition. For example:

0.4mm Nozzle: Initial layers up to 0.3mm enhance adhesion.

0.15mm Nozzle: Maximum initial layer of 0.11mm demands extreme precision, magnifying build plate leveling challenges.

Smaller nozzles exacerbate first-layer difficulties due to reduced tolerance for Z-height miscalibration.

Line width typically matches the nozzle diameter, but adjustments can address specific needs:

Standard Practice: A 0.4mm nozzle uses 0.4mm line width.

Experimental Tweaks: Increasing line width by 10% (e.g., 0.44mm on a 0.4mm nozzle) may improve surface finish but risks over-extrusion. For drastic changes, switching nozzles is often preferable.

Top/Bottom Line Width adjustments can resolve gaps in upper layers. Reducing this setting slightly (e.g., 0.35mm on a 0.4mm nozzle) encourages tighter extrusion paths, minimizing voids on flat surfaces.

While most slicer settings (e.g., wall thickness, infill density) remain unchanged for general use, niche scenarios may warrant adjustments:

Material-Specific Tuning: Flexible filaments like TPU often require reduced speeds and increased line widths to prevent buckling.

Hardware Limitations: Budget printers benefit from conservative layer heights (e.g., 0.2mm) to mitigate Z-axis inaccuracies.

The 3D printing community continually refines best practices, encouraging experimentation with slicer parameters. Documenting successful adjustments ensures reproducibility across projects.

Layer Height: Balance speed and quality within 25–75% of nozzle diameter.

Z-Axis Hardware: Match layer heights to leadscrew pitch for precision.

Initial Layer: Prioritize adhesion with thicker first layers.

Line Width: Align with nozzle size but experiment cautiously.

By understanding these principles, users can optimize prints for efficiency, reliability, and quality across diverse applications.

Some materials are naturally more brittle than others due to their polymer composition and the fiber content percentage. Fiber-reinforced filaments like Fiberon™ ASA-CF08 and PPS-CF10 are particularly brittle on the spool and require careful handling. Other blends may show better flexibility and feedability. The brittleness can be affected by storage conditions, manufacturing processes, or extended time under vacuum-sealed packaging that partially dehydrates the polymer.

If your filament is snapping or showing signs of brittleness, there are a few steps that can help restore performance:

Dry the material before printing. Use a filament dryer or oven at the recommended drying temperature for several hours to remove absorbed moisture. Drying can improve layer adhesion and reduce snapping.

Remove the outer 50 grams of filament if the spool has been vacuum sealed for a long period of time. The outer winding can become more brittle due to long-term tension or dehydration.

If you receive a Polymaker spool that is too brittle to use right out of the packaging, please contact [email protected] for assistance.

The more brittle the filament, the less suited it is for multi-path feeding systems such as the AMS. Brittle materials should have a straight and unobstructed path to the extruder, avoiding sharp bends or kinks. Even small twists can create localized stress and cause the filament to snap. It is often better to feed directly from the spool without long PTFE tubes if possible.

Removing the top cover on certain printers, such as the Creality K1, can also allow the PTFE tube to move more freely and relieve tension on the filament. For Bambu Lab printers, users can follow the manufacturer’s PPA/PPS printing guide for additional handling advice: https://wiki.bambulab.com/en/h2/manual/PPA-PPS-printing-guide

Some extruders apply more torque or filament bending during feeding, which can quickly lead to filament breaks. On the H2D printer, only the left extruder should be used when working with brittle filaments. The right extruder applies more stress, increasing the likelihood of snapping. Some other extruders may also struggle with stiff, fiber-reinforced filaments. Choosing an extruder design that minimizes twisting and provides consistent tension is key for smooth printing of brittle materials.

When printing with CF or GF-filled filaments:

Use hardened steel or ruby-tipped nozzles to handle the abrasive fibers without excessive wear.

Print at slightly higher temperatures within the recommended range to improve flow and layer adhesion.

Reduce print speed by 25–50% for smoother extrusion.

Ensure a gentle filament feed path, preferably using a direct drive extruder for greater control.

Keep moisture under control, as even fiber-filled materials benefit from consistent drying.

By handling these materials carefully and optimizing filament routing, users can maintain feed reliability and produce high-strength, dimensionally stable parts even with the most brittle engineering-grade filaments.

Carbon fiber (CF) and glass fiber (GF) filaments offer high stiffness and dimensional stability but are more brittle on the spool, requiring careful handling.

Brittleness is influenced by polymer composition, fiber content, storage conditions, and long-term vacuum sealing.

To reduce brittleness, dry the filament thoroughly and consider removing the first 50 g of old or dehydrated material.

Avoid complex feed paths; brittle filaments should follow a straight, low-friction path to the extruder without sharp bends.

Some printers, like the H2D, should use only one extruder (left) for brittle materials due to reduced torque stress.

Use hardened steel or ruby nozzles, slightly higher print temperatures, and slower print speeds (25–50% reduction) for consistent extrusion.

Store and dry filaments properly to maintain reliability and achieve durable, high-strength printed parts.

Surface resistivity is a key property defining an ESD safe material’s performance. It measures the resistance to electrical current flowing along the surface of a material and is expressed in ohms per square (Ω/sq). Unlike volume resistivity, surface resistivity only relates to conductivity across the 2D surface layer. Materials with high surface resistivity are insulative, while those with low resistivity become conductive.

For ESD safe materials, an ideal surface resistivity range typically falls between 10^4 and 10^9 Ω/sq. This range allows the material to dissipate static charges effectively without becoming fully conductive. If the surface resistivity gets too low (below about 10^4 Ω/sq), the material risks behaving like a conductor, which can cause unwanted current flow and damage. Conversely, if resistivity is too high, static charge will not dissipate efficiently.

ESD safe filaments are ideal for:

Electronic housings and enclosures

Printed circuit board (PCB) storage and transport components

Jigs, fixtures, and assembly tools in electronics manufacturing

Cleanroom-compatible parts where static control is essential

Structural components in industrial and automotive sectors requiring both mechanical strength and static dissipation

Polymaker offers two notable ESD-safe 3D printing filaments:

Fiberon™ PETG-ESD:

PETG base infused with carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipation

Surface resistivity around 10^4 to 10^7 Ω/sq, providing reliable ESD protection

Suitable for electronic housings and fixtures

Recommended print temperature: 250 to 290°C with bed temperature 70 to 80°C

Higher print temperatures reduce surface resistivity, aiding dissipation

Fiberon™ PA612-ESD:

Nylon (PA612) composite filament reinforced with carbon nanotubes and 10% carbon fiber

Offers high mechanical strength (84 MPa tensile strength), dimensional accuracy, and heat resistance (HDT up to 157°C)

Surface resistivity between 10^4 and 10^7 Ω/sq suitable for static protection

Ideal for PCBs, enclosures, industrial jigs and fixtures, and cleanroom tools

Prints at 280 to 300°C with bed temperature 40 to 50°C

Printing at higher temperatures (e.g., 320°C) can lower resistivity further, potentially making parts conductive

Both Fiberon PETG-ESD and PA612-ESD show a trend where increasing print temperature lowers the surface resistivity. This means parts printed hotter have better ESD dissipation properties. However, for PA612-ESD, printing at excessively high temperatures (around 320°C) may reduce resistivity so much that the material behaves more like a conductor rather than just dissipative, which might not be desirable depending on application needs.

The dielectric constant measures a material’s ability to store electrical energy when exposed to an electric field. It is analogous to how much water a sponge can hold; a higher dielectric constant means the material can store more electrical energy. This property is frequency-dependent and influences signal transmission. Materials with a high dielectric constant cause more energy loss and signal distortion; therefore, lower values are preferred for high-frequency applications where signal integrity and speed matter.

Fiberon PPS-GF20 has a dielectric constant of 2.62 at 1 kHz and 2.71 at 1 MHz, which is lower than that of PPS-CF10 (4.64 at 1 kHz and 3.74 at 1 MHz). This means PPS-GF20 offers better performance for transmitting fast electrical signals with minimal energy loss, making it well suited to insulating components where high-frequency signals are critical.

Summary of Electrical Characteristics

Fiberon PPS-GF20

Dielectric Strength: 6.05 kV/mm

Dielectric Constant: 2.62 (1 kHz), 2.71 (1 MHz)

Fiberon PPS-CF10

Dielectric Strength: 0.45 kV/mm

Dielectric Constant: 4.64 (1 kHz), 3.74 (1 MHz)

Combines moderate to high dielectric strength for higher voltage insulation safety.

Maintains a low dielectric constant to reduce signal loss and enable better high-frequency electrical performance.

Utilizes glass fiber reinforcement, which is electrically insulative, unlike carbon fibers that tend to conduct electricity.

Suitable for applications requiring electrical insulation with good signal transmission, such as drone housings and other electronics where radio frequency signals must pass through the material.

Flame retardant and thermally stable with a heat deflection temperature over 230°C, adding to its suitability for harsh environments.

In summary, Fiberon PPS-GF20 provides a well-balanced insulation profile making it a strong contender for 3D printed parts requiring both electrical insulation and good high-frequency signal performance. Its superior dielectric strength and low dielectric constant set it apart from carbon fiber reinforced filaments, offering safer and more efficient electrical insulation in production-grade 3D printing materials.

This material enables new applications in electrical, automotive, aerospace, and electronics sectors by combining high-performance insulation with mechanical strength and thermal stability.

A pop-up will appear asking you to copy the import link; click Copy.

Return to ideaMaker; a template download window should open automatically.

Click “Download” to fetch the slicing profile file.

After downloading, click “Next” to open the Import Slicing Template window.

Fill in any project details as needed; the basic info will auto-fill.

Select whether to import the profile to an existing printer or create a new printer profile.

If importing to an existing printer, select it from the drop-down menu.

If creating a new printer, edit settings as required in the prompted interface.

Assign filament profiles if the slicing profile corresponds to specific filaments, or create new filament profiles as needed.

Save the template settings to complete the import.

If the download window does not open automatically, enable monitoring clipboard downloads in Preferences or manually paste the import link in the import dialog.

The imported profile will now be available for slicing with the selected printer and filament.

This method leverages ideaMaker’s integration with its online Library but local imports of .bin files are also supported via the Template menu. The interface provides onscreen prompts guiding you through each step

Organization Tools: Storing accessories in an organized and accessible location near the printer improves efficiency and convenience. Organizational tools can even be 3D printed.

Fire Extinguishing Ball: A fire extinguishing ball offers peace of mind by mitigating fire hazards associated with 3D printing. Mounting one above the printer provides proactive safety.

Teflon (PTFE) Tubing: PTFE tubing guides filament to the hotend, minimizing tangling and ensuring smooth filament flow. Upgraded tubing can be beneficial, particularly for the AMS on some closed-source printers, where the tubing can wear out over time.

FDM 3D printing has unlocked a fascinating paradox: the ability to create machines that can, in turn, create more machines. From extruder assemblies to enclosures, hobbyists and engineers now use FDM to fabricate custom 3D printers tailored to specific needs—whether ultra-fast CoreXY systems, multi-material tool-changing setups, or industrial-grade enclosures. This self-replicating capability has roots in the RepRap movement, which pioneered open-source 3D printers in the 2000s, but modern advancements like Voron builds and modular tool changers have pushed the concept into new realms of precision and customization.

RepRap Roots: Early DIY printers relied on printed parts and basic hardware, proving FDM’s potential for self-replication.

Voron Revolution: Open-source Voron printers introduced CoreXY kinematics, quad gantry leveling, and community-driven innovation, enabling industrial-grade speed and accuracy at hobbyist prices.

Tool-Changing Systems: Printers like the E3D ToolChanger and DIY similar systems such as the Voron StealthChanger allow swapping extruders, lasers, or CNC heads mid-print, enabling multi-material or multi-functional workflows.

CoreXY vs. Cartesian: CoreXY’s belt-driven dual-motor system reduces moving mass, enabling faster prints without sacrificing detail.

Enclosures: Heat-resistant materials ensure stable chamber temperatures for ABS, ASA, and high-performance filaments.

Modularity: Printed mounts, cable chains, and toolhead adapters let users upgrade components (e.g., adding a pellet extruder or high-flow hotend).

Polymaker’s engineering-grade filaments are critical for durable, heat-resistant components in custom printers.

Properties: High impact resistance, higher heat deflection (~95°C), and ease of post-processing (sanding, acetone smoothing).

Applications: Printer frames, motor mounts, and electronics enclosures needing rigidity and thermal stability.

Properties: Superior UV and weather resistance, higher heat tolerance (~100°C), and minimal warping compared to ABS.

Applications: Outdoor-rated enclosures, tool-changing docks, and parts exposed to heated chambers or sunlight.

Enclosure Compatibility: Withstand chamber temperatures up to 90°C, critical for warping-prone materials like polycarbonate.

Layer Adhesion: Optimized formulations reduce delamination risks in structural components like Z-axis braces.

Cost Efficiency: Affordable alternative to metal for non-load-bearing parts (e.g., spool holders, fan ducts).

Frame: Print belt tensioners, gantry mounts, and panel clips in ASA for dimensional stability.

Electronics: Use ABS for the control board case to shield components from heat.

Toolhead: Optimize airflow with ASA ducts resistant to hotend proximity.

Mechanical Simplicity: DIY designs use printed latches and docks to swap hotends without motors, slashing costs.

Multi-Material: Print soluble supports with one toolhead and high-temp filament with another, all in a single print.

Hybrid Systems: Add laser engravers or CNC mills to FDM bases using printed adapters.

Open-source ecosystems like Voron’s community are democratizing industrial-grade capabilities, while Polymaker’s materials ensure reliability. Whether building a compact Voron 0.2 for rapid prototyping or a Voron 350 for full-scale production, FDM empowers makers to iterate endlessly—proving that the most revolutionary tool in 3D printing is the printer itself.

By combining modular design, advanced materials, and community ingenuity, custom 3D printers are no longer just tools—they’re testaments to the technology’s limitless potential.

Nylon, also known as polyamide (PA), is a family of thermoplastic polymers valued in FDM 3D printing for their strength, flexibility, and wear resistance. Despite their appealing mechanical properties, nylon filaments are among the most challenging materials to print due to their high printing temperatures, tendency to warp, and strong affinity for moisture. Several nylon types are formulated for FDM printing, each with distinct characteristics that influence print quality, mechanical performance, and ease of use.

PA6 is one of the most common nylons used in FDM printing. It is a tough material with high tensile strength and excellent impact resistance, making it suitable for functional parts and mechanical components. However, PA6 absorbs moisture quickly from the air, which can lead to bubbles and poor layer adhesion if not properly dried. It also has a strong tendency to warp unless printed with a heated bed and enclosed chamber. Typical extrusion temperatures range from 250°C to 270°C. After annealing, PA6 parts gain improved dimensional stability and heat resistance due to increased crystallization.

PA66 is similar to PA6 in composition but has a slightly higher melting point, around 260°C. This gives it superior stiffness, wear resistance, and heat resistance compared to PA6. It exhibits low creep under load and performs well for precision mechanical parts. Like PA6, PA66 is highly hygroscopic and prone to warping during printing, so it requires dry filament storage, a heated bed (around 80°C–100°C), and an enclosure. The material hardens considerably after annealing. However, when exposed to humidity afterward, it becomes more ductile and impact resistant.

PA12 is a common engineering-grade filament that differs from PA6 and PA66 through its longer molecular chain and lower moisture absorption. This makes it more dimensionally stable and easier to print with fewer warping issues. Its typical extrusion temperature ranges between 240°C and 260°C. PA12 provides high impact resistance, very good chemical resistance, and greater flexibility than other nylons. Its lower water absorption also means it retains dimensional accuracy longer in humid environments. PA12 is heat resistant to around 180°C and responds well to annealing for further crystallization and toughness.

PA612 combines characteristics of PA6 and PA12. It offers lower moisture absorption than PA6, while maintaining greater stiffness than PA12. The result is a material well-suited for applications requiring balanced mechanical strength and stability. It is easier to print than PA6 or PA66 and less prone to warping. PA612 parts have smooth surfaces and are less brittle, making them versatile for both aesthetic and functional components. Heat resistance is moderate, generally below PA66 but above PA12.

Some nylon formulations blend multiple polyamide types or include additives to target specific goals. Fiber-reinforced nylons are especially popular: carbon fiber and glass fiber reinforcements enhance stiffness, strength, and dimensional stability while reducing shrinkage and warping. These additives also improve surface finish by limiting thermal deformation during printing. However, fiber-filled filaments are more abrasive, requiring hardened nozzles.